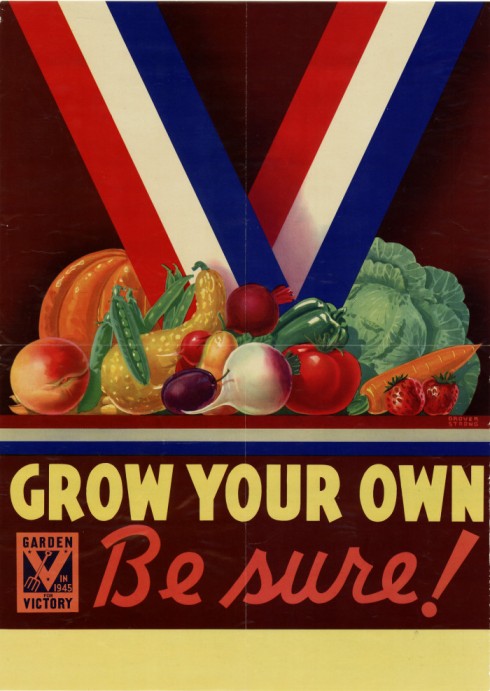

It’s been almost too hot to cook around here. Certainly, there are enough fresh summer fruits and veggies to keep me happy and full right now; our garden’s been producing a bumper crop. So, instead of a recipe, let’s begin to ponder gardens during the How to Cook a Wolf/World War II era. This will be the first in a long series because gardening is close to my heart. I imagine everyone has heard of the Victory Garden? On January 22, 1942, just the month after the US entered the war, a gardening advisory committee was appointed to direct victory garden efforts. It was nearly time to plant seeds for spring transplanting.

Home vegetable gardens, properly supervised, are recommended by the Office of Civilian Defense, Washington, D.C., but waste of seed is discouraged, it is pointed out.

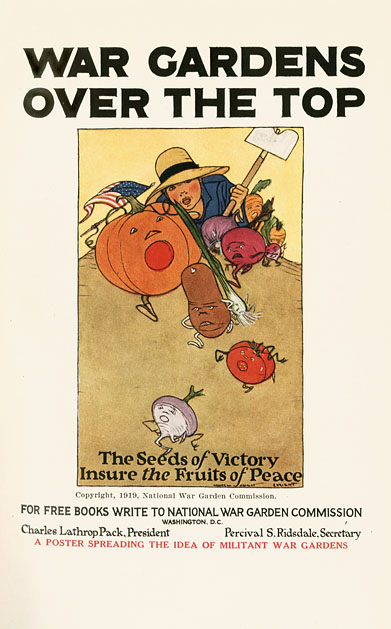

The victory garden concept was familiar to many–having been pushed during World War I, first under the name “war gardens” and, at that war’s end, “victory gardens.”

War Garden poster from Charles Lathrop Pack's The War Garden Victorious, 1919 via University of Wisconsin Digital Collections

A backyard or community garden during WWII would have been a form of insurance. The American public heard stories of starvation in war ravaged Europe and Asia. Fresh food was being funneled toward military uses. And many familiar foods were suddenly rationed. Contrary to my own beliefs about the period, many Americans (particularly those living in urban areas) were not familiar with gardening. Already, processed foods and produce waiting at the market were more popular than home grown. There had to be large scale education campaign regarding what to plant, how to do it, when, and where (more on that later).

Unlike today’s revival of Victory Gardens, they weren’t about sustainability, organic gardening, or eating locally other than by possible default. They were about immediate survival. In fact, other than fallout from leaded gasoline and deteriorating lead paint, if your current backyard garden is contaminated with lead or arsenic, there’s a good chance that the contamination was caused by someone gardening there in the past using chemicals such as the then highly-recommended lead arsenate (but that’s another post).

*Title from a Victory Garden advertisement.